Band of Brothers, Part 1: They Were Volunteers

Have you ever noticed how, for the Left, journalists are the heroes? Think of all the movies depicting them as brave soldiers of print: “All the President’s Men,” “Spotlight,” “Frost/Nixon,” “Good Night, and Good Luck,” “Reds”—and these are just the ones that immediately come to my mind. In December, Time Magazine named their People of the Year and, no surprise, they were all member of that profession.

For me, journalists aren’t heroes unless we are talking about one in, say, Russia exposing the corruption of that government or in Mexico seeking to prosecute the drug cartels. I mean, writing yet another article attacking Trump or extolling the wisdom of Obama is hardly an act of courage as they would have us believe. But journalists are like Hollywood actors—they love to celebrate themselves, and, because they possess the power of the pen, they are able to do it.

But not here.

I want to tell you the story of a group of men who are real heroes. All the more so because they were volunteers and, to my knowledge, none of them regarded the extraordinary things they did as especially heroic. Their story is largely unknown because the only time a journalist accompanied them, he was killed before he could file his report. (That was a brave journalist.) Those who didn’t die on the battlefield generally died in obscurity, unheralded by the country that sent them to war. But they are certainly remembered here in South Korea, the country they fought to save.

When the communists crossed the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, they caught American and South Korean forces completely unaware. General Douglas MacArthur, Commander of the United Nations Forces in South Korea, immediately perceived a weakness in American military tactical thinking. Unfortunately, the enemy had perceived it, too, and had greatly exploited it. Having drastically reduced the size of our ground forces following the end of hostilities in 1945, Americans believed the next war would be fought from the air with long-range bombers and via submarines with the use of tactical warheads. The Korean War, however, taught us that this war, like all others before it and since, would have to be fought on the ground. MacArthur, alarmed by the North Koreans’ liberal and effective use of commandos who penetrated UN lines and carried out missions of sabotage, assassination, and destruction, realized that the United States had no equivalent fighting force. After World War II, the Army Rangers, America’s first and only special forces unit, were decommissioned.

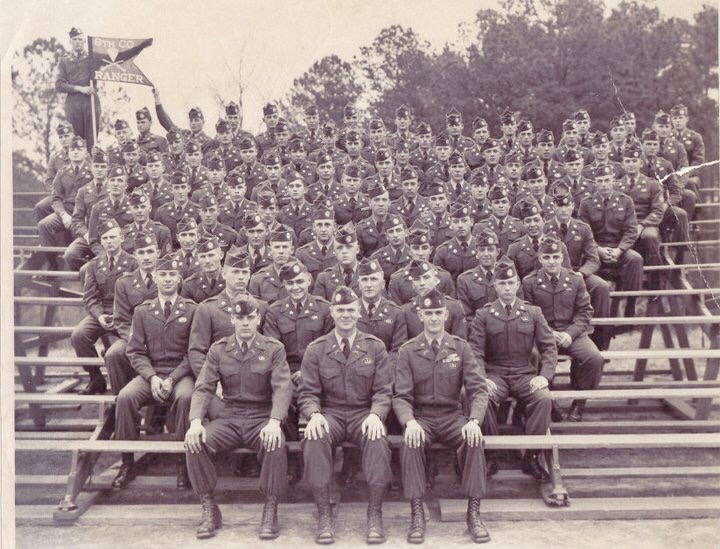

8th Ranger Company, Fort Benning 1950. It is sobering to realize that most of these men would not make it through the coming battles.

8th Ranger Company, Fort Benning 1950. It is sobering to realize that most of these men would not make it through the coming battles.

MacArthur ordered a new Ranger force be created with all possible speed. Within months of the outbreak of war, the Ranger Training Command (RTC) was established at Fort Benning, Georgia. (The CIA was eager to take a lead role in the training of these soldiers, but the Army denied them any role whatsoever.) The qualifications were rigid. Criteria included men of experience and in whom leadership qualities had already been identified; excellent physical fitness and stamina; initiative; under the age of 30; already airborne qualified; and preferably unmarried. Furthermore, according to an internal Department of the Army memo, “The men would all be volunteers with high intelligence ratings, would receive twenty percent extra pay, and be trained to handle demolitions.” Volunteers for the military know that combat is a possibility; but these men were made to know that combat was a certainty.

The invasion of South Korea was thought by many in Washington to be a diversionary tactic designed to lure American reserves away from Europe before an all-out Russian invasion of that continent. For that reason, the 82nd Airborne was kept in reserve and ready for rapid deployment at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, while the 101st Airborne was sent to Korea. Because of the 82nd Airborne’s proximity to Washington, these men were often called on for parade duty to impress foreign and domestic dignitaries. Evidently tired of the spit-and-polish routine and ready to fight, when the call went out to the 11th and 82nd Airborne Divisions for volunteers who were “willing to accept extremely hazardous duty in the combat zone in the Far East,” more than 5,000 men put their names on the roster. This is a remarkable testament to the men of that day.

It must be understood that these men were already deemed to be America’s best. They were volunteers for the Army, had survived boot camp, and then went on to volunteer for the airborne and survived that rigorous training, too. Many had already seen combat in the Second World War. Now they would face the stiffest tests of physical and mental endurance the United States Army had ever devised. To put them through the paces, the Army called on Rangers of the previous generation.

Bear in mind that this is before there were such things as Green Berets, SEALs, or Delta Force. These were much later creations. This was to be America’s one and only elite fighting force. As such, the training was, according to historian Mir Bahmanyar, “ruthless.” The training for Rangers was expensive by the standards of the day and brutal by the standards of any day. It was designed to approximate the most extreme elements of warfare and to put the men under tremendous physical, mental, and emotional duress:

“Physical conditioning and foot marches were constant. The idea was to prepare a company to move 40-50 miles, cross country, in 12-18 hours, depending on the terrain…. During training, there was in the background a Jeep with a white flag. Anyone who decided he did not want to, or could not, continue had only to go sit in the Jeep. No one would harass or mock him. He would be driven away, and his personal gear removed from the barracks before the other men returned.”

No man would be forced to be a Ranger. And many did take a ride in that Jeep. As the weeks passed, more than 4,100 of those who had volunteered, tough men all, either quit or were weeded out of the program. Those remaining were trained in all the weapons within the allied and enemy arsenals, demolition, survival, evasion, navigation, close combat, use of foreign maps, escape, jungle warfare in the swamps of Florida, mountain warfare in Colorado, and numerous other aspects of war.

8th Ranger Company ready to be sent into battle 1950

Discipline in the conventional military sense was not emphasized in Ranger training. The American model of military discipline is largely derived from a Prussian tradition that seeks to instill instinctive obedience to commands so that in the pressure cooker of combat a man does not have to think, he simply does what he is told to do because he has done it repeatedly and because he fears his officers more than the enemy. In conventional army training, soldiers are taught to work in coordination with other units. By contrast, the Rangers of 1950 were selected largely on their ability to act independently, confidently, and with initiative. This is because they would have to operate without the support of other units and almost entirely behind enemy lines.

As might be expected, such men are not easily managed and were frequently in trouble with local authorities for their antics. Crossing the Chattahoochee River from Fort Benning into Phenix City, Alabama, they engaged in binge drinking, bar fights, “skirt chasing,” pranks and vices of every kind. The base commander understood that these men were, out of necessity, thoroughbreds, but even his patience was sorely tested. The RTC, which often ran interference for these young warriors, was told to rein them in before things got out of hand.

Soldiers stationed at Fort Benning have a long history with Phenix City, a place Secretary of War Henry Stimson called, “The wickedest city in America”—and in the 1940s and 50s, it might have been. According to The Washington Post, “The toughest soldiers in the world became suckers at Phenix City’s illegal attractions, where their drinks were spiked and their pay stolen.” In 1940, Patton threatened to roll his tanks across the Chattahoochee and “flatten” that city’s jail if they did not release his men. When it became apparent that he meant it, they were promptly released. In this case, it is not clear who was victimizing whom, but the RTC didn’t bother with such details. If these boys could find time and energy for extracurriculars across the river in this southern Sin City, then there would be more forced marches and greater sleep deprivation. Men learned to function on two hours sleep, to sleep while marching, and to carry 120 pounds of gear on long patrols and jumps. Any exercise that took longer than the time allotted was penalized with a deduction of that time from the next rest period. Needless to say, trouble with local authorities stopped and more men tapped-out with a ride in the ever-present Jeep with the white flag.

Captain James Herbert was a recruiter attached to the RTC. As he interviewed volunteers and watched their performance, he made a list of those men who impressed him most. When Captain Herbert was put in charge of the yet-to-be-formed 8th Infantry Ranger Company (Airborne), he pulled out his list, his “Dream Team,” and submitted it. Pulling a few strings, he got not only the pick of the airborne units, he got his pick of Rangers. Not surprisingly, 8th Company had the highest qualification scores in the history of the Ranger Training Command. At graduation, 8th Company was required to do a low-level night jump over heavily forested Fort Benning, dangerous in the best of circumstances, but in this case the jump was so low that reserve parachutes could not be used if the main one failed. Twenty-two Rangers were injured on that jump and another killed. It took five days to locate his body. Fort Benning is roughly 190,000 acres. Finding a dead man is no easy task, and it wasn’t until the Rangers themselves searched the forest that his body was recovered.

Airborne Rangers jump at Fort Benning 1950

Graduates of the 1950 RTC should not be confused with the more than 10,000 military personnel who wear Ranger tabs (that is, the Ranger shoulder patch) today and who do not serve in Ranger units. This is no slight to those who wear them. But as any Ranger will tell you, there is a difference between passing the Ranger course and serving in a Ranger unit, especially today where the standards have been watered down for political reasons. These men were truly elite as indicated by the high washout rate and the fact that of the 500,000 soldiers of the United Nations serving in the Korean War, there were never more than 700 Rangers.

On March 5, 1951, 8th Ranger Company shipped out for Korea from San Francisco on a miserable voyage of sea sickness. An LST took them ashore at Inchon, a port scarred black by the American bombardment and landing there the previous September. A staff officer of the 24th Infantry Division stood and watched as these new shock troops made their way inland. Seeing them up close, faces painted black for camouflage, weighed down with enormous quantities of supplies, belts and backs bristling with knifes, hand grenades, Browning Automatic Rifles, and M1 Garand semi-automatic rifles, he turned to Captain Herbert and told him that his men looked like they had marched straight out of the fires of hell. Henceforth, 8th Ranger Company was known as the “Devils.”

Very soon, they would make a similar impression upon the enemy.