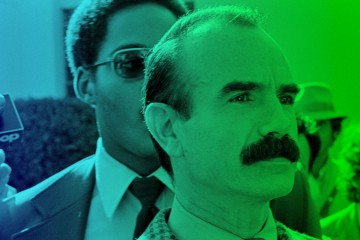

World Economic Forum chairman Klaus Schwab (center) with his Harvard mentor Henry Kissinger and former UK Prime Minister Ted Heath

(NOTE: This series originally appeared in The Daily Wire.)

The biography of Klaus Schwab, founder and chairman of the World Economic Forum, is murky at best. Several portraits of Schwab emerge in any effort to find out precisely who he is:

The avuncular misunderstood philanthropist and lover of humanity; a secret Nazi avenging his country’s defeat in a war that he can still remember; the hard-driven politician-at-large hellbent on turning his brainchild, the WEF, into an office of global governance; or the smarmy Mr. Networker Guy who likes nothing more than rubbing elbows with the rich and famous with himself as the master of ceremonies.

So, then, who is he?

Klaus Martin Schwab (1938- ) was born in Ravensburg, Germany the same month that Hitler’s Wehrmacht marched into Austria. His father, Eugen Schwab, was the managing director of Escher Wyss AG. Under Eugen’s direction, the company, with the use of slave labor, manufactured water turbines for Norsk Hydro, the center of the Nazi effort to produce an atomic bomb with heavy water.

From this slender evidence many have assumed that Klaus Schwab is himself a Nazi. This is unfair. Besides, his honorary doctorate from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beersheva, Israel suggests otherwise. Such simplistic explanations won’t do here. There is nothing in what is publicly known about the German engineer to suggest he is a megalomaniac in any conventional sense. On the contrary, his résumé, replete as it is with awards, seventeen honorary doctorates, and a knighthood, indicates a life of achievement.

But we don’t need evidence that he is the illegitimate son of Eva Braun or one of the Boys from Brazil to understand him. The truth is simpler.

Klaus Schwab was born in a time and in a country corrupted by the idea of perpetual human progress and utopianism. He was nurtured in a world where governments mobilized whole populations for mammoth projects; in which scientific advancement was still regarded with optimism rather than foreboding; and of elites who were intoxicated by the feeling that they were on the cutting edge of history and human achievement.

“In the age of social Darwinism,” wrote the late historian Jacques Barzun, “the combination of the ideas of struggle, of historical evolution and of progress, proved irresistible.”

Especially to Germans. Is it merely coincidence that the two great pretenders to world domination in modern times, Marxism and fascism, were both born in Germany[*], and that now, a third, arises from that same country? Certainly not. And both Marxism and fascism claimed a scientific basis and aspired, as Schwab has said of his “Great Reset,” to “revamp all aspects of our societies and economies, from education to social contracts and working conditions.” In this, Klaus Schwab is very much a child of mid-twentieth century Germany.

All of this is exacerbated by the fact that he is also very much a typical Leftist.

Where the average person wakes up in the morning, grabs a cup of coffee, and begins organizing their day, the Leftist wakes up and begins thinking about how to organize your day, too. Schwab is like the guy who runs your HOA and is constantly issuing edicts on recycling or telling you to take down your Christmas decorations, but with a continental-sized—no, planetary-sized—ambition and ego to match it. Imagine the audacity of a person who thinks he is, by virtue of his virtue, entitled to decide the minutest details of your life: what you do own—or, more accurately, what you don’t; what you eat; your level of privacy; and whether or not you have a microchip implanted in your brain.

This is Klaus Schwab.

But not contented with annoying people on an individual basis, he formed a club of likeminded people in an effort to establish the HOA from hell: the World Economic Forum. These are people who are all infected by what political philosopher Karl Popper—who, ironically, taught George Soros at the London School of Economics—called “the spell of Plato.” You see, in every intellectual’s literary paradise, from Plato’s Republic to Thomas More’s Utopia, the masses are ruled by a dictatorship of self-appointed “enlightened” elite.

Just read, as I have, Schwab’s books (co-authored by Thierry Malleret): The Fourth Industrial Revolution (2016); COVID-19: The Great Reset (2020); and The Great Narrative (2020). Of the many things one finds there, chief among them is a contempt for democracy. Schwab and his coterie do not believe in liberty for the individual, only for the collective, which is to say, no liberty at all.

In books that appear to have been printed at Kinkos, contain no indices, and are as riveting as a TV manual, it soon becomes clear that Schwab (and Malleret) is not an original thinker. The term “The Great Reset” was coined by urban studies theorist Richard Florida. The idea being that great economic crises bring about corresponding societal convulsions. But Florida receives no mention in COVID-19: The Great Reset. Schwab’s twist on the theme is to view such catastrophes as an opportunity to reinvent everything, top-down.

Then, as I began drilling down into The First Global Revolution (1991), an academic report produced by the highly influential think tank The Club of Rome, it appeared that Richard Florida had lifted the concept, if not the term, from what the authors of the report called “The Great Transition,” the definition of which fit that of Florida’s.

That said, Schwab clearly possesses a deep knowledge and understanding of science and technology. Even at his age (84), you need only watch a video of him talking on these subjects and he ranges easily between them with apparent mastery. But his books and the literary references that run through them—Boccaccio, Daniel Dafoe, Hemingway—leave me cold because you get the impression that he doesn’t know any of them as one knows old friends. They are simply quote-mined and harnessed to his agenda.

Behind all the big ideas and Davos hobnobbing one begins to detect an element of sophistry; a man whose mind lacks the formal moral education that only the humanities, and, I believe, Christian literature, can impart. Schwab, I realized, is a technocrat.

If this sounds less dangerous to you, it shouldn’t. Klaus Martin Schwab has been greatly influenced not only by the milieu of his childhood—which gave rise to his grandiose proclamation “The future is built by us!”—but also by a series of apocalyptic academic works to be explored later in this series: The Predicament of Mankind (1970), The Limits to Growth (1972), The First Global Revolution, and the previously classified National Security Study Memorandum (NSSM) 200 (1974) written by Schwab’s mentor, Henry Kissinger.

They all have a single theme: global overpopulation. The First Global Revolution puts it more bluntly: “The real enemy, then, is humanity itself.”

In his classic on the Reign of Terror, Yale historian R.R. Palmer wrote of the well-intentioned Maximilien Robespierre:

He was preoccupied with an inner vision, the thought of ills which it seemed to him could easily be corrected, the picture of a world in which there should be no cruelty or discrimination…. [His] sympathies were always with the underdog; he believed in equality seriously and profoundly…. He had the virtues and the faults of an inquisitor. A lover of mankind, he could not enter with sympathy into the minds of his own neighbors.

Under Robespierre’s guidance, the Committee of Public Safety, a misnomer if ever there was one, guillotined roughly 17,000 people.

And they did it all in the name of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.

[*] I am, of course, aware that fascism is often considered of Italian origin. But it cannot be doubted that its fullest expression was in Hitler’s Germany.

WAIT! Do you appreciate the content of this website? We are a nonprofit. That means that our work is made possible and our staff is paid by your contributions. We ask you to consider supporting this important work in an ongoing basis or, if you prefer, perhaps you will drop a few buck in our “tip jar.” All contributions are tax-deductible.