Raphael’s The School of Athens in the Vatican

Making good use of my time in Rome, I thought I would continue to offer you what I hope are useful historical and cultural insights from The Eternal City. Today, I focus on one of the most spectacular pieces of art of the High Renaissance: Raphael Sanzio’s The School of Athens.

Don’t like art?

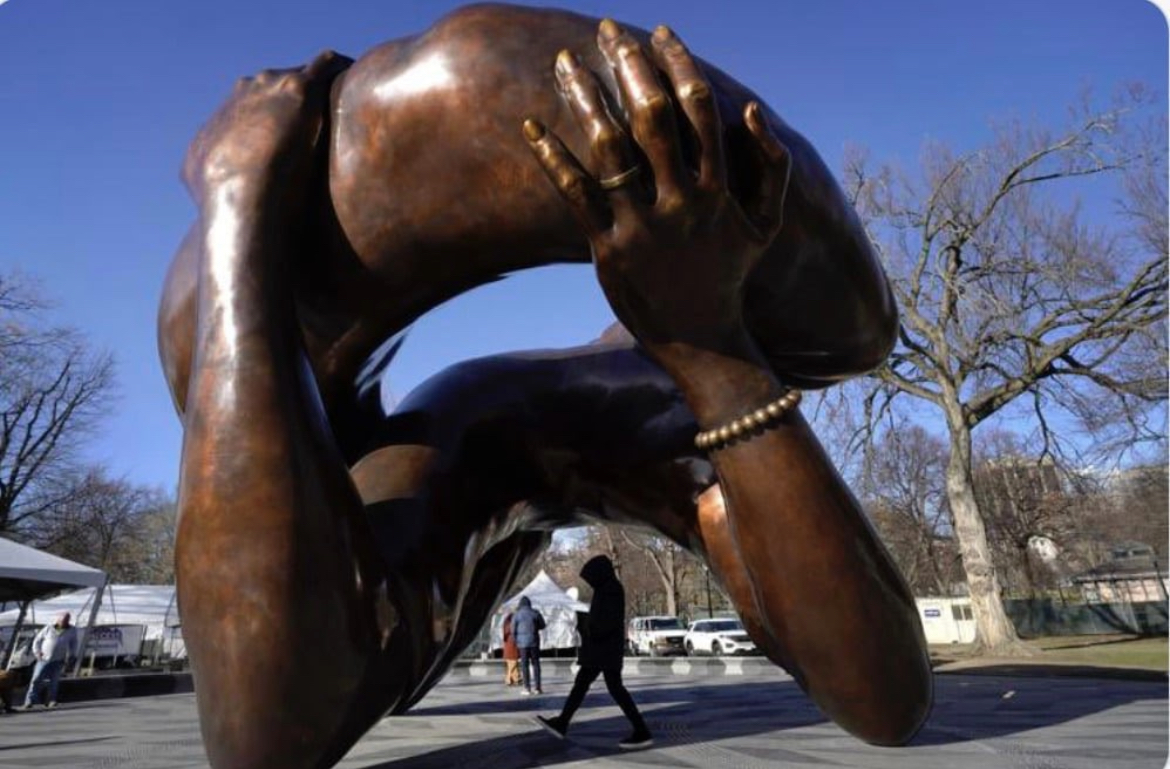

Much of it isn’t likable. Consider this recently unveiled “art” in Boston. It cost taxpayers millions and supposedly honors the memories of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King. Detractors have called it “Hands Holding a Giant Turd.” I cannot disagree with the description.

Is this art or a public disgrace?

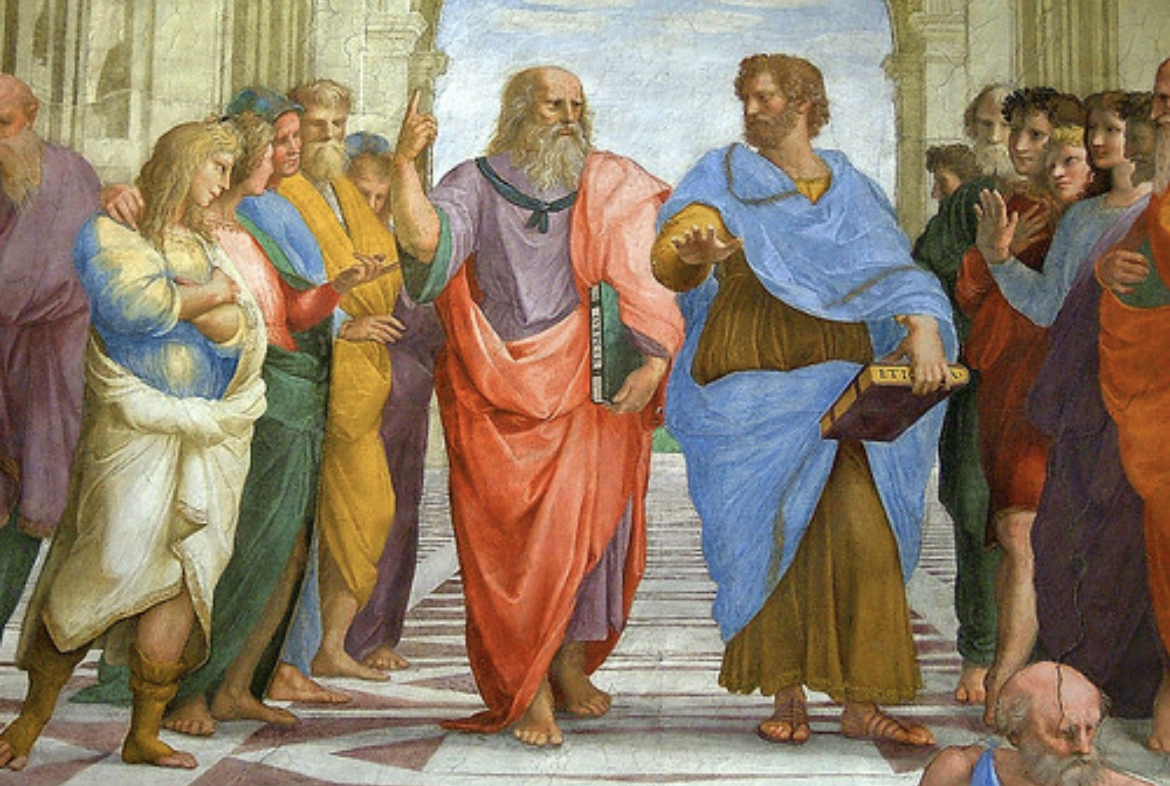

The School of Athens, however, is different. It is the work of a master, and it is found in the Vatican apartments of Pope Julius II (1503 – 13). “The Warrior Pope,” as Julius was justly called (played by Rex Harrison in the epic film The Agony and the Ecstasy with Charlton Heston), commissioned a series of paintings from the 26-year-old Raphael (1483 – 1520). From 1509 – 1511, he did this one.

Let me tell you what so intrigues me about this painting and why, seeing it once again only yesterday, I am captivated by it. The Renaissance, meaning “rebirth,” was a revival of classical Greco-Roman philosophy, architecture, and artistic styles. And nowhere is that more evident than in this 25’ x 16.5’ fresco.

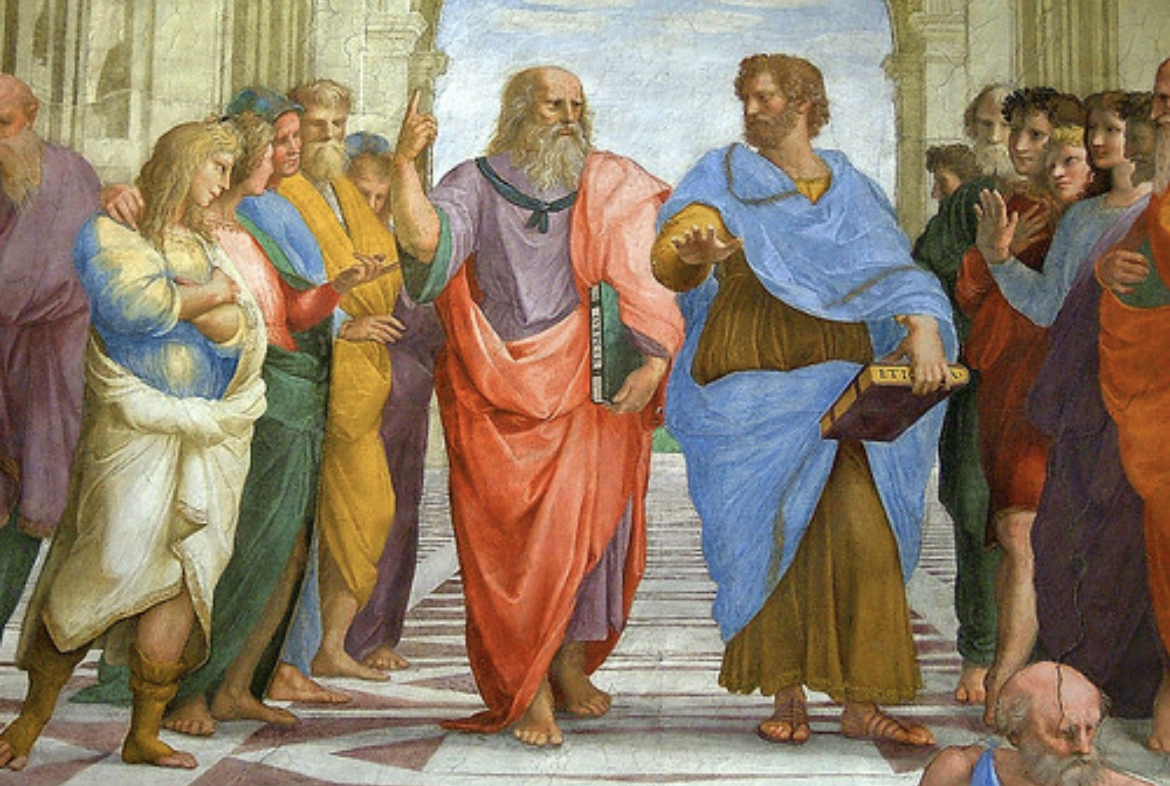

Raphael painted it in such a way as to draw our eyes to the two figures at the center: Plato and his pupil, Aristotle. Plato (428 – 348 BC) walks pointing up, emphasizing the unseen world. Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) extends his hand downward, emphasizing the tangible. Plato wears colors suggesting the ethereal: fire and cloud. Aristotle the colors of earth: water and soil.

Plato (left center) and Aristotle (right center) are the focal point

Around them are the great men of science, mathematics, and philosophy of the classical world like Epicurus, Pythagoras, Euclid, and Zeno. Raphael has divided these great thinkers according to which man at the center their thought most closely aligned (as you look at the painting): Platonic thinkers on the left, Aristotelian on the right. So great was the respect for Plato and Aristotle in the Renaissance that these men are portrayed here as the hub of all thought that is worth thinking. This fresco is, above all else, about them.

I’ll not name all the figures depicted here. And it’s impossible to do so because Raphael left us no notes to interpret it. Even so, I’ll point out a few things often overlooked in any discussion about this work.

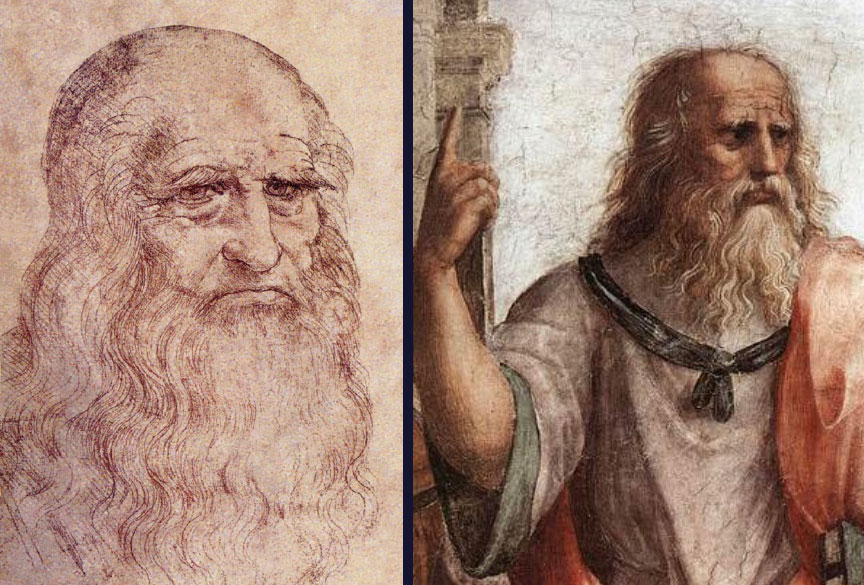

Leonardo’s Self-Portrait (left) was reproduced by Raphael on Plato (right) within The School of Athens

First, note how Raphael has given Plato the face of Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519). We know this from da Vinci’s self-portrait. I have placed both works side by side to make comparison easier. Da Vinci was an acknowledged genius in his own lifetime and was still very much alive when Raphael was hard at work on this Vatican fresco.

Michelangelo’s face on Heraclitus

Raphael has also included, in the foreground, Heraclitus with the face of Michelangelo. Michelangelo was painting the Sistine Chapel at the same time that Raphael was painting The School of Athens and was, like da Vinci, celebrated in his own lifetime. I personally think this was an afterthought, perhaps added by Raphael’s students, because it doesn’t really fit—the dimensions and angles of his desk seem wrong, the figure is oversized, and he is out of place. Some speculate that Raphael was forced to add it by his patrons. But we simply don’t know.

Two more figures that might interest you. They are subtle, but they flank the enormous painting and they share a trait: both are looking at us.

Raphael’s self-portrait in The School of Athens (left) and his Self-Portrait (right)

The first is thought to be Raphael himself. As with Leonardo, I have placed Raphael’s Self-Portrait next to his self-portrait within The School of Athens. (I reversed the image of the Self-Portrait to make comparison easier.) The young man is watching us, as if gauging our reaction to his work. The face is soulful, searching, as if he is not sure we will approve.

The mysterious woman. Who was she?

The second is a woman, the only woman in the entire scene. Some think it Hypatia of Alexandria, an astronomer of the fourth and fifth centuries. Others think it a man, specifically, Francesco Maria I della Rovere, who was the Duke of Urbino at the time. But having seen a woman before—as well as Titian’s portrait of Rovere—I’m pretty sure this is one of that species. Her presence has led to speculation that she was a favorite mistress Raphael misrepresented to his patrons as Hypatia or some other woman from history.

What it tells us about the church of Raphael’s time

A bigger question is this: Why were pre-Christian, that is, pagan, philosophers given such prominence in, of all places, the Vatican?

Why was pagan thought celebrated within the church?

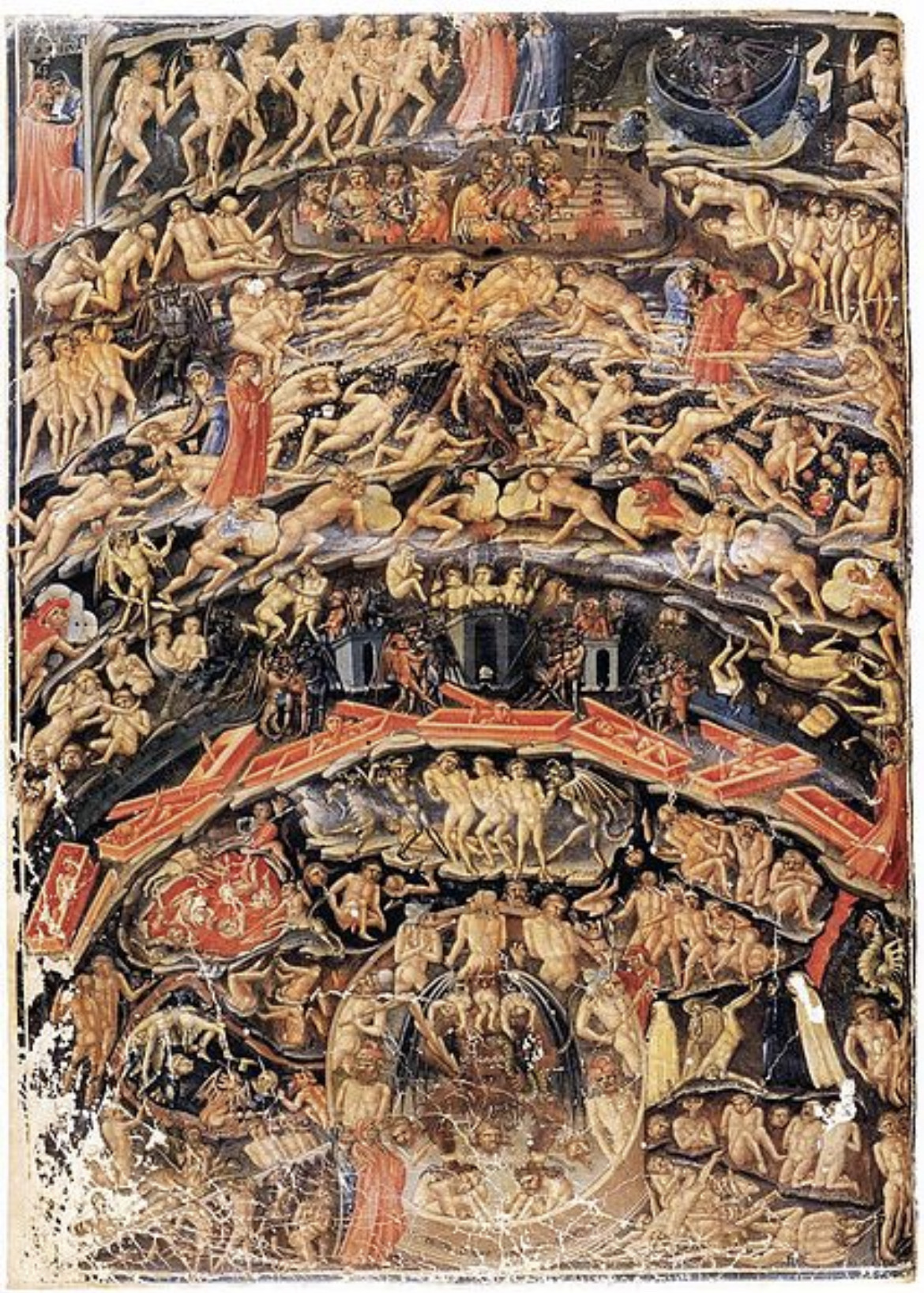

The churches of the Middle Ages and High Renaissance were infatuated with Greek philosophy. Take, for example, Dante’s Inferno where Hell is comprised of nine concentric circles of punishment. The first is Limbo. Those found here were mostly ignorant of Jesus Christ. They are virtuous pagans living in a lesser Heaven.

From there, each circle gets progressively worse until we reach the ninth, the bottom, the place of treachery where Lucifer himself is tormented day and night forever.

Dante’s Inferno

Dante puts Plato and Aristotle (among others) in the First Circle of Hell. Since they weren’t Christians, he had to put them in Hell no matter how much he hated to do so. But he and his contemporaries admired them because they had taken natural revelation as far as it could go without special revelation. So, he gives them the least punishment possible: Limbo. And, so it is with The School of Athens. It honors the Greek philosophers as was the fashion of the Renaissance.

To demonstrate the degree to which pagan thought had penetrated the church theologically, let’s look at a doctrine central to Catholicism: transubstantiation.

Transubstantiation maintains that the bread and wine of the sacrament of communion literally become the body and blood of Christ when consecrated by a priest. This became official Catholic doctrine at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215.

To defend the doctrine, Aristotelian philosophy was employed. Aristotle made a distinction between a given object’s substance and its accidents. The substance of an object is what it is made of, its essence you might say. The accidents of that same object are in its appearance, shape, smell, taste, feel.

Perhaps you can see where this is going. The Catholic, that is, the Aristotelian, explanation for transubstantiation was that while the accidents of the bread and wine do not change—to us, they still appear, taste, and smell like bread and wine—the substances of both are miraculously changed into the body and blood of Christ.

Interestingly, Christian Europe would outpace and then abandon Platonic and Aristotelian thought on several points as a dead end just as the Islamic World was beginning its own love affair with Greek philosophy. But the very presence of these figures in the Vatican reveals the depth of the church’s admiration at this time.

Some in the church, however, objected to this pagan influence among a litany of other things. One, an obscure German monk named Martin Luther, would nail his 95 Theses on a church door in Wittenberg about six years after Raphael finished The School of Athens.

Another, John Calvin, ironically, a classicist by training who was born the same year that Raphael started this grand Vatican project, ruthlessly attacked the syncretism within the church that this painting celebrates.

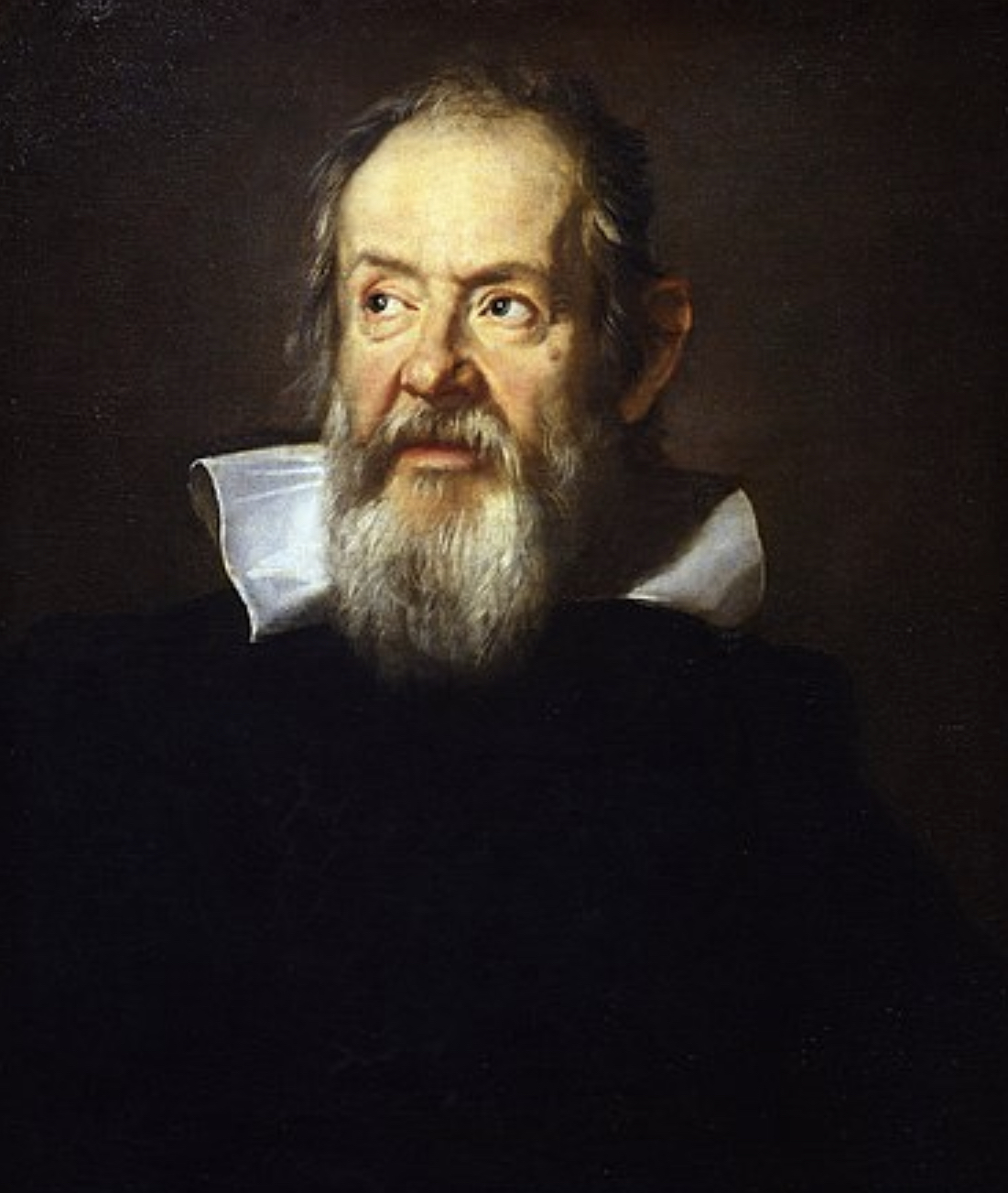

Galileo

And finally, came a man born in 1564, the same year that Michelangelo and Calvin died, who would demolish once and for all Aristotle’s conception of the universe:

Galileo.

So, you see, a painting is worth a thousand words. Or, in this case, 1,364 words.

WAIT! Do you appreciate the content of this website? We are a nonprofit. That means that our work is made possible and our staff is paid by your contributions. We ask you to consider supporting this important work in an ongoing basis or, if you prefer, perhaps you will drop a few buck in our “tip jar.” All contributions are tax-deductible.