“Intolerant dogmatism is one of the main obstacles to science…. Indeed, we should not only keep alternative theories alive by discussing them, but we should systematically look for new alternatives. And we should be worried whenever there are no alternatives — whenever a dominant theory becomes too exclusive. The danger to progress in science is much increased if the theory in question obtains something like a monopoly. But there is an even greater danger: a theory, even a scientific theory, may become an intellectual fashion, a substitute for religion, an entrenched ideology.”

—Karl Popper, The Myth of Framework

I returned to Birmingham, Alabama from Oxford, England and hit the ground running. John Lennox had expressed openness to my invitation but he had made no commitments. Before he would do so, he wanted me to demonstrate that I was “serious” about what I had proposed. I was very serious indeed. But what if I went to the considerable trouble of planning a debate and other events around it and he turned me down anyway? That nagging fear lingered in the back of my mind but I suppressed the thought.

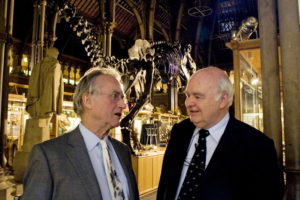

I went to my board and supporters, the people who would have to fund these events, and told them about Lennox and why Alister McGrath would not be suited to our purpose. None had ever heard of John Lennox. Did I have any CDs of him? Perhaps a video? I had nothing. A brief search on the internet yielded nothing. I emailed Lennox to ask him if he had anything. Nothing. It was as if this man did not exist. He pointed me to a church in London where he had recently spoken. Ask them, he said, if they had recorded his lecture. They had recorded it, and they promptly mailed a CD to me.

None had ever heard of John Lennox. Did I have any CDs of him? Perhaps a video?

It was awful. Not the lecture. The quality. It sounded like Lennox was speaking on the New Orleans coast as Hurricane Katrina was making landfall. He could barely be heard over the swishing and whirring. Perhaps he wasn’t speaking at a London church at all but in the particle accelerator at CERN? One look at the man and it seemed plausible.

With some embarrassment I played it for my board. A look around the room told the story. Men grimaced and frowned at the obnoxious sound emanating from my CD player.

“If you listen carefully, you can hear what he’s saying,” I implored with maybe too much enthusiasm. “It’s really good!”

They were not convinced and urged me to shut it off with all possible speed.

“So you say McGrath won’t work, eh?” one asked.

I shook my head in the negative.

“But you really are sold on this guy?”

“Yes. Very much. He’s perfect. Trust me.”

And on the strength of that recommendation they were all in.

At this point in the history of Fixed Point Foundation, I must remind you, there were no staff other than me. There was no event planner, no administrative types, no tech people. I had a slick brochure and a closet-sized office. (It was literally closet-sized. When I moved out, the office next door knocked a hole through the adjoining wall and made it their supply closet.)

I felt the appropriate place for this debate was a university, and why not my undergraduate alma mater, Samford University? I promptly made an appointment to see University President Thomas Corts. On the scheduled day, I entered his office with brochure in hand. President Corts came around from his desk and directed me to a sofa while he took a chair opposite me. After the usual pre-purpose-of-meeting exchanges, he came to the point.

“What can I do for you?”

I took a deep breath. “We are wondering if the university would like to host a debate on Intelligent Design?”

“What do you have in mind?” His face was inscrutable.

I told him about Professor Lennox, his credentials, his views so far as I then understood them, and the type of event we had in mind.

“Who would debate him?”

“I haven’t decided that yet. Perhaps someone from the science department? Maybe someone else.”

After a few minutes he said, “We will host it. Start your planning.”

We stood, shook hands, and I left giddy. This had seemed like a longshot. My brochure must have impressed him!

Within a short time I arranged events at the McWane Science Center, several churches, and more, all of it leading up to the main event, the debate at Samford University.

But was Lennox in? Would he do it?

I sat down and hammered out an email to him bulleting out all that I had arranged, describing each event in detail, and making it clear that I had put my neck on the line. Fearing my email would just get lost with all the others this man likely received, I needed to end it with a punch. Something that would require a response. I had it! I added this cheeky sentence:

“So, Professor Lennox, as you can see, I am serious. Are you?”

As I would later learn, John Lennox was, at that moment, having tea with his wife, Sally, on his back porch in Oxford when a ding on his Mac laptop notified him of my email. Reading it, he pushed the laptop across the table to Sally.

“Read this,” he said.

Sally read it and laughed out loud.

“This man has the measure of you, John!” she chuckled. “You cannot let him down. He has made good on your bargain, and you must go!”

Meanwhile, on my side of the Atlantic, things were heating up. With word out on Samford’s campus about our planned debate, AL.com, in a dubious article of the type at which they specialize, had splashed across the front page:

“[Samford] Faculty Protest Creation Speech.”

It wasn’t a “creation speech” as the author of the column well knew. It was a debate. And the mischaracterizations didn’t stop there. Unbeknownst to us, sometime prior to my meeting with him, Dr. Corts had announced his retirement, and Samford University was in the midst of a hotly contested search for his successor. There were suggestions that Fixed Point Foundation was some sort of leviathan manipulating the search process.

That this was absurd was obvious to any who were familiar with us and what our objectives were. We had no such power or influence, much less a desire to involve ourselves in the university’s internal politics. But with this article came pressure. As intended, it had whipped a tempest in a teapot into a genuine controversy. I was nervous that President Corts and/or Professor Lennox would withdraw. They didn’t. Corts was in China when the storm broke. But his intuition was such that he had anticipated my concern. He left a message for me:

“I told you that you had my support. You do. Don’t worry about the university front. I will deal with that. Just remain focused on your task and deliver an outstanding event.”

The Samford University faculty Listserv was full of hysterical denunciations of Lennox and the event. I was aware of this because, as a graduate of Samford, I knew a lot of people there and they were forwarding the correspondence to me. It made for highly entertaining reading. But I was also disappointed and embarrassed for the faculty. Isn’t a university about ideas? Why were they so afraid? If they were so confident in the absolute truth of their views, why not subject them to scrutiny – perhaps we would all be convinced? It was this sort of arrogance that had led us to step into the Intelligent Design controversy in the first place. Karl Popper (quoted above) was right: “a theory, even a scientific theory, may become an intellectual fashion, a substitute for religion, an entrenched ideology.” Evolutionary theory had become a religion, and its proponents as dogmatic as any Muslim cleric. You simply were not allowed to question their secular theology.

It was this sort of arrogance that had led us to step into the Intelligent Design controversy in the first place.

John Carroll, the Dean of Samford’s law school, weighed in on the electronic debate then lighting up faculty computers across the campus, and offered a tidy summary along with a sober warning, saying, as I recall:

You [i.e., protestors] had better be right and this Lennox turns out to be the crackpot you say he is, because if he isn’t, you’re the ones who are going to look like a bunch of narrow-minded bigots.

I was asked to attend a meeting with representatives of the faculty. Still possessed of a cheery naiveté, I was sure that this was all a big misunderstanding. It wasn’t. We met in the science building. I sat on one side of an old wooden library table and they sat on the other. For an hour they asked me about Fixed Point, our objectives, and Lennox. Having failed to get President Corts to cancel the debate, they tried to coerce me into canceling it. This was an ambush. I was angry and immovable. I had the university president’s support, and while I would have liked the faculty’s, too, I didn’t need it.

Then came the veiled threats. The faculty wouldn’t participate, they wouldn’t allow the debate to take place anywhere other than the chapel, they would discourage their students from attending, etc. I have worked with students my entire career, and I knew that this would have the opposite effect of that which they intended. Nothing arouses the interest of young people more than to tell them that they shouldn’t do this or smoke that. I needed to promote this event, and they were doing it for me. Like an old Southern children’s story, I felt like exclaiming, “No, please don’t throw me in the briar patch!”

And it didn’t stop there. Following our meeting, some members of the faculty circulated an advertisement denouncing the debate. This, too, was sent to me by students who wanted us to know what they were up against. The faculty leading this charge had overplayed their hand, grossly overestimating their own influence (and popularity) with students. As if this were not enough, a member of the faculty, a Max Babers (a geographer formerly known as Max Beavers), accosted me in a local coffee shop. I did not know who he was, but he knew who I was and decided to let loose a torrent of abuse as I stood in line waiting to place an order. He looked like a homeless man. He seemed unhinged. When I realized he was a member of Samford’s faculty, I was shocked. Offering a few conciliatory words, which made not the slightest dent, I got my coffee and left.

When Professor Lennox arrived in February 2006, he wondered aloud, and not for the first time, what in the world I had gotten him into. I was no less surprised by the furor. Regardless, I had picked the fight, now he would have to go into the arena and win it. I could only hope he was equal to the billing I had given him.

He was.

Very soon, Dean Carroll’s warning, unheeded, would prove prophetic.